Africa-focused ride-hailing startup, SafeBoda, is no longer safe in Uganda, where it could call home. In Nigeria, where it has recently expanded to, government has chased its likes away from major cities. In Kenya, where it hopes to hedge its losses in Nigeria and Uganda from, it has now died. And yet, death is the unimagined just two years after launching in Kenya! In a tweet laden not only with defeat but also with dints of dissolving hope, SafeBoda has bidden farewell to its Kenyan riders. Kwaheri! is the right word in Swahili, meaning Goodbye!

And although the company has blamed COVID-19 for worsening its woes in the east African nation, there appears to be more to this than meets the eye as Kenya even lifted its pandemic-induced lockdown a month before Uganda.

But one thing is clear in all these: East Africa has a problem with cases of startup shut downs; and Africa as a whole, a problem with bike-hailing.

In February this year, CanGo, the Rwanda-based startup that delivered orders to its clients, folded up, even with an armoury of $1.1m from investors. This was before Jumia, Africa’s first $1 billion dollar company, did similar things with all its operations in another east African country, Tanzania as well as in Rwanda.

SafeBoda, Kenya: The Timelines

- Founded in 2014.

- In June 2018, it launched operations in Kenya and released an update which allowed credit purchase using M-PESA.

- In June 2019, it introduced an alternative way to buy airtime using SafeBoda credit.

- In August 2019, SafeBoda launched a feature to allow people to share credit with other people. It also introduced a feature which improved logistics using the ‘Send’ feature where customers could send parcels to other people.

- On 18th December 2019, it introduced the food feature where customers could order food from.

- In 2019, it expanded to Mombasa, Kenya’s second largest city.

Understanding Why This Is Significant

SafeBoda’s sad exit in Kenya is a big blow for many reasons, but first it represents a huge burden on digitalised bike-hailing services in Kenya going forward. Kenya has almost stretched its limits on internet penetration, with over 87.2% of the population (the highest in Africa) connected to the internet. Poverty, at the rate of 36.1%, however, still remains a major issue, although the country’s economy is the largest and most developed in eastern and central Africa.

Compared to Rwanda, where CanGo previously operated, there are about 3,724,678 internet users as of December 2018, representing about 29.1% of the population, with about 39 percent of the population living below poverty line and 16 percent living in extreme poverty.

A direct implication of this is that by all standards, there are no reasons why SafeBoda should not have succeeded in Kenya, all things being equal.

Why Shut down?

There are many probable reasons why SafeBoda might have called it a quit in Kenya.

First, it appears that almost everybody in the east African country owns a boda boda (commercial motorcycle), a trend which increased shortly after the Kenyan government allowed, in 2016, the importation of motorcycles into the country without any import duty. According to Kenya National Bureau of Statistics’ report in 2017, registrations of newly imported motorcycles rose by about 80% in the first seven months of that year. The report also showed that 146,757 motorcycle units, up from 86,286 during the similar period in 2016 were imported. This means that Kenyans had been importing an average of 16,500 units every month since January, 2017 when the import duty was lifted. This trend may have likely continued, making mockery of Safeboda’s 4000 motorcycles.

Second, funding glut is not a remote cause, but an immediate one. With the coronavirus ravaging startups across the world, a fact clearly pointed out by the startup in its farewell statement to Kenyans, it is only logical to shut down less productive branches, to save funds.

Investors, too, have increasingly displayed less appetite towards bike-hailing ventures in Africa, given their chequered history on the continent. The government of Nigeria’s Lagos State has, for instance, recently, by a stroke of a regulatory pen, erased over $150 million investments in that sector.

Similar funding worries were also expressed by Barrett Nash, CanGo’s co-founder, following the startup’s demise in East Africa.

And although SafeBoda had announced it has seen over 1 million downloads in all its three countries of operations, it is arguable that Nairobi and Mombasa have little to contribute to this. With an average GDP per capita of approximately $6000, over 5 million residents of those cities can afford to ditch Safeboda for car-hailing companies like Uber or Bolt.

Third, SafeBoda may have failed to get its main business model — bike-hailing — right in Kenya, even with all its value extensions and features such as its “Send” feature, among others. There were already strong competitors in other verticals it attempted to onboard onto its platform. Glovo, for example, is already a big player in the logistics sector; M-PESA is, itself, one of the biggest mobile money operators in the world. Jumia Food is also a leading player in the food delivery industry in Kenya.

Fourth and again, bike-hailing riders are still the king! Unarguably, whenever the failure of bike-hailing startups in Africa is being written, the riders and their management should not escape their own strokes of condemnation. Even with the introduction of policies on earnings and savings through the SafeBoda Sacco, a life cover of Sh100,000 per rider, an accident cover and enrollment for regular training at community hubs, the riders still appeared to have other motives. Below is a sneak peek into this assumption:

SafeBoda Kenya business shutdown SafeBoda Kenya business shutdown SafeBoda Kenya business shutdown SafeBoda Kenya business shutdown SafeBoda Kenya business shutdown

SafeBoda Is Sitting On A Time Bomb

Hacking off its Kenyan operations does not mean that SafeBoda is anywhere home and dry. Its wound is still simmering in neighbouring Uganda where government has recently flashed it the greatest threat of its life.

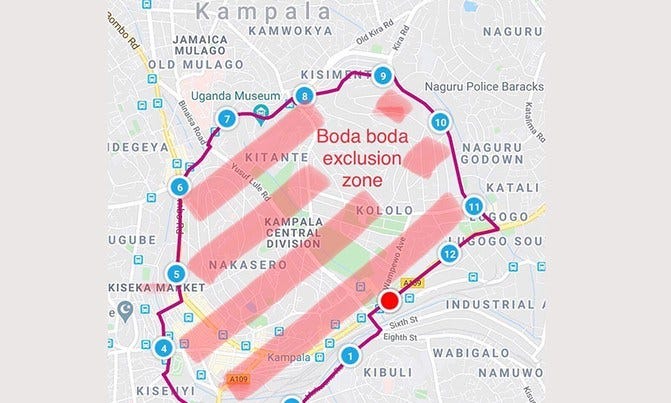

In exactly the same fashion, the city of Kampala, Uganda’s capital, which is home to about 1.5 million people, attempted to do what Nigeria’s most populous city — Lagos — did to its famously known okadas back in February this year — the city’s government banned them from operating on its highways.

A widespread agitation against the directive banning commercial cyclists from accessing the Kampala city center and surrounding places, however, has led to the suspension of the proposed ban. This would have and may still severely cut deeply into SafeBoda’s remaining life.

“In light of the presentations, KCCA in consultation with other key government agencies has come up with a roadmap that will facilitate operation of the digital companies as well as streamlining public transport. The roadmap entails a validation exercise for digital companies and make recommendations to each for the city to achieve a harmonized transport system,” the directive read in part.

“Cabinet approved Boda Boda Free Zone where All Boda Bodas are prohibited from entering/accessing,” it further read.

All moves came after the Ugandan government, earlier in May this year, through the State Minister for Kampala, Kampala Lord Mayor Erias Lukwago, Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) and the Ministry of Works and Transport, issued unimplemented guidelines expressing its intentions to force all traditional commercial motorcyclists (locally more known as “boda boda”) to go digital or cease to exist.

Kampala is Uganda’s largest city, population-wise (1.5 million), and by far ahead of cities like Gulu, Entebbe, Lira, Mbarara or Nansana which have a combination of not up to 1,000,000 people. (Note: only about 18 million Ugandans, representing about 40.1% of the population have access to the internet.)

In Nigeria, where SafeBoda’s remaining life outside Uganda is, the future is blurry, and all tied to government’s body langauge. Currently, the startup is now operating in the Nigerian southern city of Ibadan.

The ban, in Lagos, on bike-hailing nevertheless still remains a deadly blow on ride-hailing startups in Nigeria. Lagos holds about 15.2% of Nigeria’s entire internet population (14,192,283 subscribers).

What Does The Future Look Like For Bike-Hailing Startups In Africa?

Perhaps, would this be the best time African startup founders looked away from launching bike-hailing startups given the continuing instability around bike-hailing business across the continent?

Opay had, for instance, after several insinuations in the media about its troubled Super App, come clear, declaring that “some of our business units including the ride-hailing services: ORide, OCar as well as our logistics service OExpress will be put on pause.”

Opay’s move was the first sign that all was not well with existing bike-hailing startups in Nigeria whose operations had been severely affected by government ban, even though they had all pivoted to other Nigerian cities, apart from Lagos, including branching out to other business verticals such as logistics.

To put it clearly, the list of threatened investments in the African bike-hailing industry is mind-blowing.

In May 2019, Rise Capital with Adventure Capital, First MidWest Group, IC Global Partners and other investors led a $5.3 million investment in Gokada, an on-demand motorcycle taxi startup in Nigeria. A month after, this was exceeded by another motorcycle startup, MAX.ng which raised a $7 million funding round led by Novastar Ventures, with the participation of Japanese manufacturer Yamaha, an investment which brought the startup’s total funding to $9 million. Inspired by the funding MAX.ng planned introduction of electric motorcycles. And yet five months later, in November 2019, Opera’s Africa-focused fintech startup added a new $120 million to its $50 million series A round which it raised in June of 2019, backed by Chinese investors.

In Uganda, leading bike-hailing startup SafeBoda has up to $1.3 million in funding with most of the investments coming from Allianz X, the digital investment unit of international financial services provider Allianz Group. Go-Ventures, a venture fund whose cornerstone investor is the Indonesia-based “Super App” company GO-JEK also participated in that investment. Investment in Safeboda was Allianz X’s first ever investment in an African-headquartered company

However, notwithstanding all these, Tunisia’s bike-hailing startup InstiGo has recently gone ahead to secure renewed confidence of investors in the continent’s bike-hailing ecosystem. The startup raised a new $1 million from Capsa Capital Partners and other investors, early July, although it plans to use the investment to explore deeper into other market opportunities, including car sharing.

But it continues to look like bike-hailing startups in Africa still have a pretty long future, if not an entirely foggy one.

Charles Rapulu Udoh

Charles Rapulu Udoh is a Lagos-based lawyer who has advised startups across Africa on issues such as startup funding (Venture Capital, Debt financing, private equity, angel investing etc), taxation, strategies, etc. He also has special focus on the protection of business or brands’ intellectual property rights ( such as trademark, patent or design) across Africa and other foreign jurisdictions.

He is well versed on issues of ESG (sustainability), media and entertainment law, corporate finance and governance.

He is also an award-winning writer