What African Ride-Hailing Startups Must Learn From Uber And Lyft’s Frustration In California

To African ride-hailing startups, California’s new employment law is biting hard. No one expected Uber’s long tested business model, which was built on the basic principles of the gig economy, to change overnight, but this is happening. Under California ’s new law, nobody — drivers or gig workers — working for Uber or Lyft, or indeed any other freelance platforms now known or yet to be known, should simply be referred to, again, as an independent contractor. The new class for all of them— of course, subject to a three-pronged test — is “employees”; and this is a heavy word. Heavy because, going forward, Uber and other e-hailing companies, for instance, may be in their last throes of death defending their over $200 billion business from sinking into extinction not just in the US’ wealthiest state, but also in other states and countries inspired by California’s new path.

What Is This California’s New Employment Law All About?

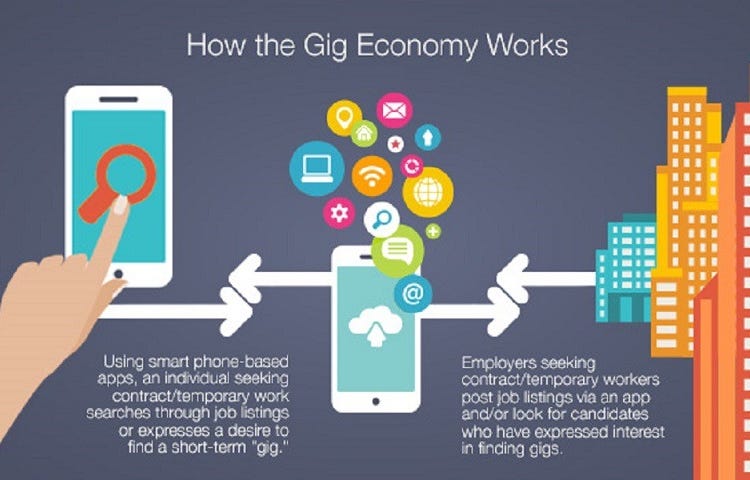

The quirkiest way of summarizing California’s new employment law is that it has reclassified, disrupted, removed and destroyed everything you know about the gig economy, such that if you decide to register with Uber as a driver, in say Lagos, Nigeria, for instance, you would no longer be seen as working independent of the e-hailing company, but as its employee; even though the car is yours and you command some influence on how you choose to do your work. And of course, as an employee, you’re entitled to daily or monthly wages or salaries, and are subject to Uber’s control and authority. But this is the most simplistic interpretation of the law.

In Details, Here Is What The New Law Fully States

- The law, entitled Assembly B5, or simply AB5, has changed the criteria for being an independent contractor in California.

- Now, for a company to classify a worker as an independent contractor, it must prove three things (you may hear this being called the “ABC Test”). If they can’t, then the worker is treated as an employee.

- First, companies must prove that “the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work.” In other words, companies can’t manage contractors the way they would employees. As an example, if a catering hall contracted a chef to prepare food events, but controlled how the chef prepared the food — giving them custom orders from customers, giving a strict schedule for production, and instituting standard procedures — they would likely not satisfy this part of the test.

- Second, companies must prove that “the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.” This means that a company like Uber has to prove that driving users from location A to location B is outside the company’s usual course of business. Uber said as much in a press release, contending that the company is actually a “technology platform for several different types of digital marketplaces.”

- Third, the companies must prove that “the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed.” For example, an electrician doing contract electrical work is still a contractor. It’s unclear if ride sharing or meal delivery companies will be unable to clear this bar.

- Consequently, under this new law, all of these independent contractors could earn employee status if the companies can’t satisfy the ABC test.

This is why Uber and Lyft, and others are fuming and have threatened to suspend all their operations till further notice, save for a timely reprieve from a court in California, which recently ruled that the word “independent contractors” still be tagged along with the drivers pending the determination of an appeal before it.

All the wailing ride-hailing companies know the implications of the law finally scaling through: Lyft, alone, has more than 300,000 drivers in California. Uber said in a recent blog post that its number of active drivers per quarter in California is about 209,000. Now, with the law in place, Uber and Lyft, and others are expected to cater to these drivers’ needs, as is expected of employers, including but not limited to granting them holiday and sick pay; overtime; health insurance; as well as other range of employment protection, benefits and their attendant tax implications. It would really be a serious reshaping of these companies’ finances.

One thing may likely save Uber and Lyft though: a ballot, known as Proposition 22, will be put up in November, at the same time as the US presidential election, inviting any eligible voter in California to vote, for or against, on whether Uber and Lyft be granted an exemption from the law.

Although Proposition 22 envisages some changes to give drivers minimum-wage standards, limited health benefits and flexibility, while maintaining the rideshare model, if voters disagree with it — especially as it is the labour groups that are pushing for Assembly B5 — Uber and Lyft, and other ride-hailing firms, may have to fold up — an option, not likely to be on the table as California, alone, accounts for about 16 percent of Lyft’s business, according to John Zimmer, Lyft’s president.

The companies may, alternatively, have to opt for other types of models. Already, plans are being mulled by Uber and Lyft to license their technology to those who want to operate fleets of ride-hailing cars in California, under a franchise model; but that, itself, may be too expensive. One analyst, Mr. Ives of Wedbush Securities has estimated that implementing any changes to the existing rideshare model would cost Uber $500 million a year and Lyft $200 million a year. This is even compounded by the fact that both companies have remained unprofitable, as per reports, and have also been gravely affected by lockdowns associated with the coronavirus pandemic.

If Assembly B5 Finally Sails Through At The End Of The Day, It Could Have Domino Effects Across Jurisdictions

Although Bradley Tusk, president of Tusk Ventures and an early Uber investor, had told The Verge, late last year that “a domino effect [is] not just possible,” it’s beginning to look like his statement was poorly premeditated. There are already signs on the wall. Joining California Attorney General Xavier Becerra in his case against Uber and Lyft, which alleges that the ride-hailing companies have misclassified their drivers as contractors in violation of the new state law that went into effect this year, are city attorneys from San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego. Although these are major cities in the state of California, there are strong indications that the success of the case may send a strong signal to drivers in other US states — and across several other jurisdictions around the world, which have, until now, been looking for ways to muffle competition in an already saturated market . This may consequently necessitate major changes in their laws to accommodate their own peculiarities.

For one thing, the influence of California in the US and around the world cannot be overstated. Apart from the fact that the state is the largest of any US state — economy-wise — it is also the world’s fifth largest economy, behind Germany and ahead of India. The state is also home to “Silicon Valley” and some of the world’s most valuable companies such as Apple, Google, NetFlix, Twitter, Uber, and Facebook. A natural argument from the success of Assembly B5 at the end of the day would, therefore, be that if the tech-supported gig economy was inspired by the innovations brought about by Silicon Valley, it wouldn’t make much sense to continue to hold onto the traditional definition of the concept, when those who first laid its foundation have gone ahead to redefine it.

Although Uber and Lyft have argued that they are simply tech platforms and are not transportation businesses, the argument does not hold firm for all seasons. Uber, for example, has had to bend its operations in Germany and Spain to fit into the country’s transportation rules, which permit working with fleets, even though it is a tech platform. One thing needs to be pointed out here: although the Assembly B5 law does not apply to only rideshare business models, but to the entire gig economy, it seems, however, that the rideshare model would be the most affected given that it is often seen as being at the front lines of the economy.

“AB5 is riding two waves,” says Alex Rosenblat, a technology ethnographer and author of Uberland: How Algorithms are Rewriting the Rules of Work, to The Verve, “ a longstanding effort to restore workplace protections to misclassified workers; and it comes on the heels of the techlash.”

Rosenblat further argues that while the California law is about more than just Uber and Lyft, the drivers became the face of all workers exploited by giant tech companies. “That’s why AB5 is a symbolic and remarkable shift towards accountability, in labor and in tech,” she said.

On his part, Bradley Tusk adds that “ if the sharing-economy companies can’t radically reframe the narrative from ‘evil Silicon Valley powerhouse vs workers’ to ‘what this actually means for workers and consumers vs groups looking to profit from the changes,’ they’ll keep losing everywhere.”

How Does Assembly B5 Affect African Ride-sharing Startups?

There are already signs on the wall that California’s Assembly B5 law may be replicated in Africa. At least, governments of all major African countries and cities housing the continent’s gig economy ecosystems have spent the past five years caressing and testing their power to make laws that will severely touch tech startups wherever they may be located in the world. Lagos, Africa’s most valuable startup ecosystem, recently introduced a set of new regulations which will take off from August 27, 2020. The regulations, among other things, state that each e-hailing company must pay N8 million ($20.5k) per 1,000 cars as fresh licencing and renewal fees; that the companies will have comprehensive insurance for each driver while the driver is working with them; that a flat fee of N20 ($0.052) per trip, called a Road Improvement Fund, will be levied per trip.

Under South Africa’s National Land Transport Amendment Bill, which has been passed in parliament and sent to South Africa’s president for assent, drivers on car-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt who do not have operating licences — not driving licenses — may incur a fine as much as R100 000 ($6000) for those platforms (Uber, Bolt and others), which would definitely be levied against the affected drivers directly or indirectly.

In Ghana, from Uber to Bolt to Yango, drivers who rely on ride-hailing to sustain their livelihoods would start paying a mandatory GHC 60 ($11) annual fee, in addition to their cars undergoing roadworthy tests every six months. Ghana’s Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA), which imposed the GH¢60 ($11) annual fee noted that the guidelines will cover the current ride-hailing platforms like Uber, Bolt, and Yango and will also cover companies who intend to operate ride-hailing platforms in Ghana in the future.

Therefore, it is only a matter of time before African governments’ regulatory attention reaches across to this spectrum. This reach would, however, be faster if California’s Assembly B5 beats naysayers at the polls on November 22, 2020.

When an issue assumes a political coloration, nothing is often guaranteed; especially as political interests, clad in sweeping powers, are almost always determined to push to protect majority interests rather than those of a few; majority interests, in this case, being the groaning drivers who command large voting powers; and the few being corporations and organisations whose barking powers are never anywhere near the ballot boxes.

The Bottom Line

The best way to contain this impending disruption of the gig economy is to hear the gig workers out, in time, in the first place. As startups practising in the sector, never make their conditions so horrible that they begin to stick out their voices. It may be so overwhelming once everything converges to a head.

Charles Rapulu Udoh

Charles Rapulu Udoh is a Lagos-based lawyer who has advised startups across Africa on issues such as startup funding (Venture Capital, Debt financing, private equity, angel investing etc), taxation, strategies, etc. He also has special focus on the protection of business or brands’ intellectual property rights ( such as trademark, patent or design) across Africa and other foreign jurisdictions.

He is well versed on issues of ESG (sustainability), media and entertainment law, corporate finance and governance.

He is also an award-winning writer