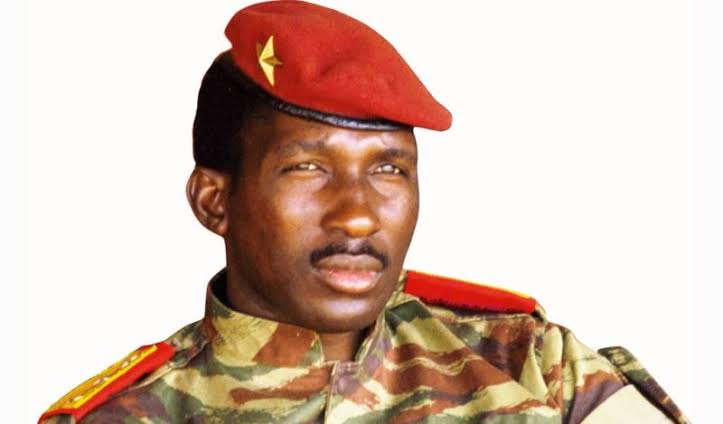

Remembering Thomas Sankara, A True African Hero

Today Africans remember with a tinge of nostalgia and anger, one of the truly people-centric leadership this continent ever had; Thomas Isidore Noel Sankara, former president of Burkina Faso. Today marks the 32st anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara, leader of the Burkinabè August Revolution which overthrew country’s corrupt military leadership in 1983.As Africans remember one of the greatest leaders to emerge from the continent, one whose life was albeit cut short; many are of the view that Sankara was the right man who came at the wrong time. A time when the cloak of imperialism was still heavy, and the African narrative did not have the African perspective.

Some say that his greatest sin was that he tried to be honest in a dishonest and highly corrupt system. Born 21 December 1949, Sankara was a Burkinabé revolutionary who presided over the affairs of the country from 1983 to 1987. A core Marxist and unarguably the most authentic pan-Africanist after the liberation fighters of the 1960’s, Sankara was viewed across Africa as a charismatic and highly iconic figure of revolution in the mold of both Che Guevara, and Fidel Castor, both of whom inspired him greatly.

Read also: Mahamadou Issoufou brings African vision to the World at the Dialogue of Civilizations

After basic military training in secondary school in 1966, Sankara began his military career at the age of 19 and a year later was sent to Madagascar for officer training at Antsirabe where he witnessed popular uprisings in 1971 and 1972 against the government of Philibert Tsiranana and first read the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, profoundly influencing his political views for the rest of his life. Returning to Upper Volta in 1972, he fought in a border war between Upper Volta and Mali by 1974. He earned fame for his heroic performance in the border war with Mali, but years later would renounce the war as “useless and unjust”, are flection of his growing political consciousness.

He also became a popular figure in the capital of Ouagadougou. Sankara was a decent guitarist. He played in a band named “Tout-à-Coup Jazz” and rode a motorcycle. In 1976 he became commander of the Commando Training Centre in Pô. In the same year he met Blaise Compaoré in Morocco. During the presidency of Colonel Saye Zerbo, a group of young officers formed a secret organisation called the “Communist Officers’ Group” (Regroupement des officiers communistes, or ROC), the best-known members being Henri Zongo, Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani, Blaise Compaoré and Sankara. After a coup which brought the military to power in 1982, Sankara was appointed Secretary of State for Information; he was attending cabinet meetings on a bicycle which endeared him to the masses. But he resigned his portfolio on 21 April 1982 in opposition to what he saw as the regime’s anti-labour drift, declaring it a misfortune to those who gag the people.

These disagreements led to another military coup on 7 November 1982 which brought Major-Doctor Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo to power, and he made Sankara the Prime Minister in January 1983, but Sankara soon fell out with the Head of State, and he was subsequently arrested and placed under house arrest with his comrades, Henri Zongo and Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani. In 1983, a group of revolutionaries seized power on behalf of Sankara (who was under house arrest at the time) in a popularly-supported coup in 1983. Sankara was made the Military President at the age of 33 to the admiration of the masses.

He hit the ground running by launching programmes for social, ecological, and economic change, and renamed the country from the French colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso (“Land of Incorruptible People”). His foreign policies were centred on anti-imperialism, with his government eschewing all foreign aid, pushing for odious debt reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth and averting the power and influence of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. His domestic policies were focused on preventing famine with agrarian self-sufficiency and land reform, prioritising education with a nationwide literacy campaign and promoting public health by vaccinating 2,500,000 children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles.

Other components of his national agenda included planting over 10,000,000 trees to combat the growing desertification of the Sahel, redistributing land from feudal landlords to peasants, suspending rural poll taxes and domestic rents and establishing a road and railway construction programme. On the local level, Sankara called on every village to build a medical dispensary, and had over 350 communities build schools with their own labour. Moreover, he outlawed female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy, as well as appointing women to high governmental positions and encouraging them to work outside the home and stay in school, even if pregnant. He encouraged the prosecution of officials accused of corruption, counter-revolutionaries and “lazy workers” in Popular Revolutionary Tribunals. As an admirer of the Cuban Revolution, Sankara set up Cuban-style Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. His revolutionary programmes for African self-reliance made him an icon to many of Africa’s poor. Sankara remained popular with most of his country’s citizens. However, his policies alienated and antagonised several groups, which included the small, but powerful Burkinabé middle class, the tribal leaders who were stripped of their long-held traditional privileges of forced labour and tribute payments, as well as the governments of France and its ally the Ivory Coast.

Read also: New $95 Million Naspers Foundry Fund Will Look Beyond South African Startups

On 15 October 1987,Sankara was assassinated by troops led by his very closest friend Captain Blaise Compaoré, who assumed leadership of the state shortly after. A week before his assassination, Sankara declared: “While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas”. While the Burkinabè August Revolution lasted a mere four years and two months, from August 1983 to October 1987, its tremendous political, economic and social accomplishments remain unparalleled. Among the realisations were clear advances in health care, gender equality, food self-sufficiency and small-scale agricultural production (with Burkina Faso became a net exporter of food stuffs), reforestation, expansions in public transport, promotion of the arts, refusal of debt, rebukes of neo-imperialism, promotion of fitness and collective practices, and more.

That these achievements occurred amidst continuous political and economic sabotages and significant material challenges, only renders the story of Thomas Sankara and the August Revolution even more emboldening for humanist struggles for wellbeing. Some of these economic successes would be noted after Sankara’s death by those institutions heralding the compulsion for neoliberal economic policies across the African continent, including in BurkinaFaso. The World Bank country report for Burkina Faso, for example, reveals the determination of capitalist actors to appropriate critical and anti-capitalist actions as their own triumphs. In the years since his assassination, international environmental movements have gained momentum and some of Sankara’s groundbreaking policies have been adopted by transnational and largely neoliberal organisations.

There has been the mainstreaming of his policies across the world, especially his insistence on the importance of gender equality for social wellbeing (or ‘human development’) and the adoption of initiatives in support of grassroots efforts to green and re-tree the Sahel, including the Great Green Wall of the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative, a project colloquially believed to have its genesis in Sankara’s ecological projects among others.

After his death, the government of Blaise Compoaré initiated a ‘rectification period’ that withdrew the radical economic and social programmes central to the revolution. Until 1998, references to Sankara were prohibited while publically the government alternately sought to discredit Sankara or to take credit for the successes of the revolution.

Before the United Nations General Assembly in1984, he said, ‘I make no claims to lay out any doctrines… I am neither a messiah nor prophet. I possess no truths. My only aspiration is twofold: first, to be able to speak on behalf of my people, the people of Burkina Faso, in simple words, words that are clear and factual. And second, in my own way to speak on behalf of the “great disinherited people of the world”’. In his yearning to create a grassroots resistance consciousness of self-empowerment, Sankara defined the tradition of hero-worship. He discontinued the practice of hanging presidential portraits in public buildings.

Till date, no African leader dead or living evokes the kind of emotion and passion especially among young people across the continent as Thomas Sankara, a true African Hero.

Kelechi Deca

Kelechi Deca has over two decades of media experience, he has traveled to over 77 countries reporting on multilateral development institutions, international business, trade, travels, culture, and diplomacy. He is also a petrol head with in-depth knowledge of automobiles and the auto industry.