In a perfect world of the gig economy, James should be able to hire a car from a rental service store, present his driving license and other certifications to Uber (a car hailing service, for instance), get registered if he is considered qualified based on a series of paper checks and tests, and take to town helping online car hailers to reach their destinations, at an automated pay rate, and of course, as long as he fully complies with the terms and conditions of his engagement with Uber. In this arrangement, although James uses the Uber hailing service as a vehicle to carry out his business, he is still considered by Uber as an independent contractor who works off the controls and the supervision of Uber, except on occasions where he is skidding off his original rules of engagement. Thus, in a gig economy, James should not be on Uber’s payroll and is not even qualified to be classified as an employee of Uber. But all that has been shaken up, disrupted by the Californian state legislature, in a landmark new bill that has just scaled through the last phase in parliament, pending an assent by the Californian state governor. If other jurisdictions draw inspiration from California’s new standards, then all logistics, transport and other similar startups that have built their business models around independent contracting would be back to square one; that is, to the previous era when there was little or no disruption.

Bradley Tusk, president of Tusk Ventures and Uber’s first political strategist, told The Verge, “A domino effect [is] not just possible, it’s all but guaranteed.”

First Here Is What The New Law Proposes

- The bill has changed the criteria for being an independent contractor.

- Now, for a company to classify a worker as an independent contractor, it must prove three things (you may hear this being called the “ABC Test”). If they can’t, then the worker is treated as an employee.

- First, companies must prove “the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work.” In other words, companies can’t manage contractors the way they would employees. As an example, if a catering hall contracted a chef to prepare food events, but controlled how the chef prepared the food — giving them custom orders from customers, giving a strict schedule for production, and instituting standard procedures — they would likely not satisfy this part of the test.

- Second, companies must prove “the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.” This means a company like Uber has to prove that driving users from location to location is outside the company’s usual course of business. Uber said as much in a press release, contending that the company is actually a “technology platform for several different types of digital marketplaces.”

- Third, the companies must prove “the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed.” For example, an electrician doing contract electrical work is still a contractor. It’s unclear if ride sharing or meal delivery companies will be unable to clear this bar.

- Consequently, under this new law, all of these independent contractors could earn employee status if the companies can’t satisfy the ABC test — which greatly increases the company’s overhead. Worker’s comp, benefits, tax implications — it would be a serious reshaping of these companies’ finances.

Applying The New Californian Rule To Similar African Startups

There is no specific legislation on independent contractors in two of Africa’s largest economies — Nigeria and South Africa. However, the English common law standards have continued to apply.

The common law recognises a distinction between a contract of service (an employer-employee relationship under which the employee subordinated his or her services to the authority of the employer — a locatio conductio operarum) AND a contract for services (a principal — independent contractor relationship where the former contracts the latter to deliver certain services and there is no subordination by the contractor, who instead is answerable to the service deliverables contracted for — a locatio conductio operis).

Who Therefore Is An Employee Or Independent Contractor In South Africa?

Since there is no express law that draws a distinction on who an independent contractor or employee in South Africa is, courts in the country have often adopted an approach that can best be described as a “reality approach”, which involves assessing the reality of the relationship by taking account all of the relevant factors on a substance-over-form basis, the public interest and the fact that parties have no licence to artificially take themselves out of the scope of important legislation such as the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995 (“LRA”) the Basic Conditions of Employment Act 75 of 1997 (“BCEA”) and the Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998 (“EEA”) in existence in the country. Consequently, there is currently in place in the country an authoritative judgement on the issue. By the rules, in arriving at whether a person is an independent contractor or not, questions must asked on whether:

- The principal has rights of supervision and control over the contractor, i.e. whether the contractor is obliged to follow the instructions of the principal, including whether the principal is able to dictate to the contractor when he/she is required to render their services, the manner in which such services are rendered and generally whether the contractor is at the principal’s ‘beck and call’

- Whether the contractor forms an integral part of the principal’s organisation, e.g. whether the contractor participates or is an integral part of the principal’s internal management and/or staff structures; whether the contractor is ‘part and parcel of the organisation’ or whether the work done is for the business but is not integrated into it and is only accessory to it; whether the contractor would appear to an outsider to be an employee of the principal.

- The contractor is economically dependent on the principal or whether he/ she is free to derive income from other sources as well. Thus, a person who is truly self-employed cannot be economically dependent on their “employer” when he or she retains his or her ability and power to contract with and render services to other persons or entities.

Read also: From Job To Startup: How African Startup Owners Handled The Dilemma

The above three factors are not exhaustive of all the factors to be taken into consideration when considering whether a person is an independent contractor or not.

The South African parliament has however gone ahead to incorporate these three conditions (considered as presumptions which can be rebuttable) as part of South Africa’s national legislation on employment.

Consequently, under the LRA and BCEA, a person who earns less than an earnings threshold amount determined by the Minister of Labour in terms of the BCEA3, and who works for or renders services to another person, will be presumed — until the contrary is proved and regardless of the form of the contract — to be an employee of the other person if one or more of the following factors are present:

• the manner in which the person works is subject to the control or direction of the other person;

• the person’s hours of work are subject to the control and direction of the other person;

• in the case of a person who works for an organisation, the person is a part of that organisation;

• the person has worked for the other person for an average of at least 40 hours per month over the last 3 months;

• the person is economically dependent on the other person;

• the person is provided with tools of trade or work equipment by the other person; or

• the person only works for or renders services to the other person.

The effect of this classification into the status of an employee or an independent contractor is that in the Fourth Schedule to the South Africna Income Tax Act, only employees and not independent contractors are entitled to earn “remuneration”. That is, a person can only earn ‘remuneration’ if their services or duties are required to be performed mainly at the premises of the client and:

- the worker is subject to the control of any other person as to the manner in which his duties are or will be performed, or as to the hours of work; or

- the worker is subject to the supervision of any other person as to:

- the manner in which his duties are or will be performed; or

- the hours of work.

This will also mean that the independent contractor would not be part of certain benefits applicable only to employees such as a working period of not more than 45 ordinary hours in any week, fair termination of employment among others. As opposed to employees, independent contractors are only entitled to such “benefits” and terms as have been agreed to between the independent contractor and his / her client. Again, the termination of independent contracting relationships is governed only by the agreement between the parties.

Who Is An Employee Or Independent Contractor In Nigeria?

Nigeria’s case is very much the same with South Africa’s. Both countries have no legislation that specifically defines who an independent contractor is, except of course the application of the common law principles of contract of service and contract for service. Nigeria’s Supreme Court, in Shena Security Co. Ltd v. Afropak (Nig.) Ltd & 2 Others [2008] 18 NWLR (Pt. 1118) 77 SC; [2008] 4–5 SC (Pt. II) 117 has laid down the some extensive factors that should guide courts in determining which kind of contract the parties entered into –

- If payments are made by way of “wages” or “salaries” this is indicative that the contract is one of service. If it is a contract for service, the independent contractor gets his payment by way of “fees”. In like manner, where payment is by way of commission only or on the completion of the job, that indicates that the contract is for service.

- Where the employer supplies the tools and other capital equipment there is a strong likelihood that the contract is that of employment or of service. But where the person engaged has to invest and provide capital for the work to progress that indicates that it is a contract for service.

- In a contract of service/employment, it is inconsistent for an employer to delegate his duties under the contract. Thus, where a contract allows a person to delegate his duties there under, it becomes a contract for services.

- Where the hours of work are not fixed it is not a contract of employment/of service. See Milway (Southern) Ltd v. Willshire [1978] 1 RLR 322.

- It is not fatal to the existence of a contract of employment/of service that the work is not carried out on the emjployer’s premises. However, a contract which allows the work to be carried on outside the employer’s premises is more likely to be a contract for service.

- Where an office accommodation and a secretary are provided by the employer, it is a contract of service/of employment.

These factors, as in South Africa’s case, would also provide a guide in considering whether the benefits and the responsibilities expected of the independent contractor or the principal as the case may be.

The Implication of The Positions of The Law in the Two Countries In Relation To California’s New Rules

The above explanations are important because in both countries, courts will not usually be bound by the labels that parties chose to attach to their relationship or defer to the declared intent of the parties in this regard, whether in their contract or elsewhere. Thus, stipulating in a contract (or elsewhere) that a relationship is one between independent contractor and principal or referring to the contract as an independent contractor or consultancy agreement, when the relationship between the principal and the contractor is, in reality, one between employee and employer, does not make the relationship any less of an employment relationship, and vice versa.

Comparing South Africa and Nigeria’s case on the one hand and California’s case on the other, it is obvious that California’s case went too far in establishing who an independent contractor is. For instance, apart from the fact that in California’s case, companies must prove “the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work,” companies must also prove “the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business” and that “the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed.”

While the first test, i.e. that of control, appears to still conform to the basic standards used in determining who an independent contractor is, the second and the third tests tend to have looked beyond these basic features of control and supervision to question the need for independent contractors when the engaging companies could as well themselves do the work. This, in all ramifications, is predatory legislation, and which would be very hard to found followership in other jurisdictions.

Do African Startups Need To Re-Adjust In Time?

As a matter of strategy, remodelling the nature of services African startups offer on the basis of this new Californian legislation would, of course be a matter of long-term strategic plans for startups. African government’s demeanour towards this is such that it does not seem that they are very much in a hurry to change the status quo. Unlike, other jurisdictions that have clear-cut definitions of who an independent contractor is, most African countries are yet to come up with even a legislated definition of the term. California’s case cannot be unrelated to the continuing agitations by Uber drivers in the state, of exploitation by the multi-billionaire dollar car hailing company. In March, Uber agreed to pay $20 million to settle a nearly six-year-old lawsuit by California and Massachusetts drivers over their classifications. The case is McRay v Uber Technologies Inc, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, №19–05723.

Uber, rival Lyft Inc and food delivery service DoorDash, on their own, have pushed for separate legislation to boost driver pay and benefits while preserving their independent contractor status.

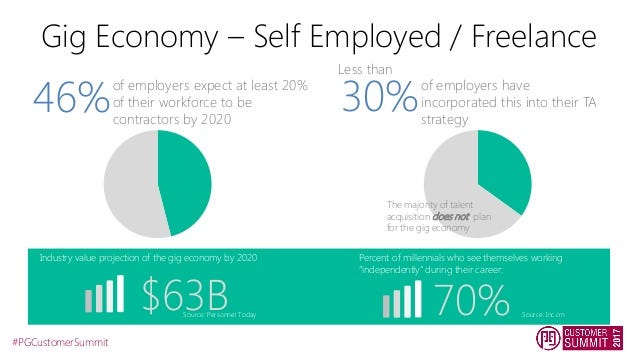

African startups with similar business models as Uber, Lyft Inc, DoorDash, Fiverr, Upwork, and others should however, keep this in mind. It not only has the capacity of suddenly bringing to an end the gig economy, it also has the potency of sending all new disruptive business models that rely on public workforce into an abrupt extinction.

Charles Rapulu Udoh

Charles Rapulu Udoh is a Lagos-based Lawyer with special focus on Business Law, Intellectual Property Rights, Entertainment and Technology Law. He is also an award-winning writer. Working for notable organizations so far has exposed him to some of industry best practices in business, finance strategies, law, dispute resolution, and data analytics both in Nigeria and across the world.