The startup ecosystem in Eswatini still seems far off.

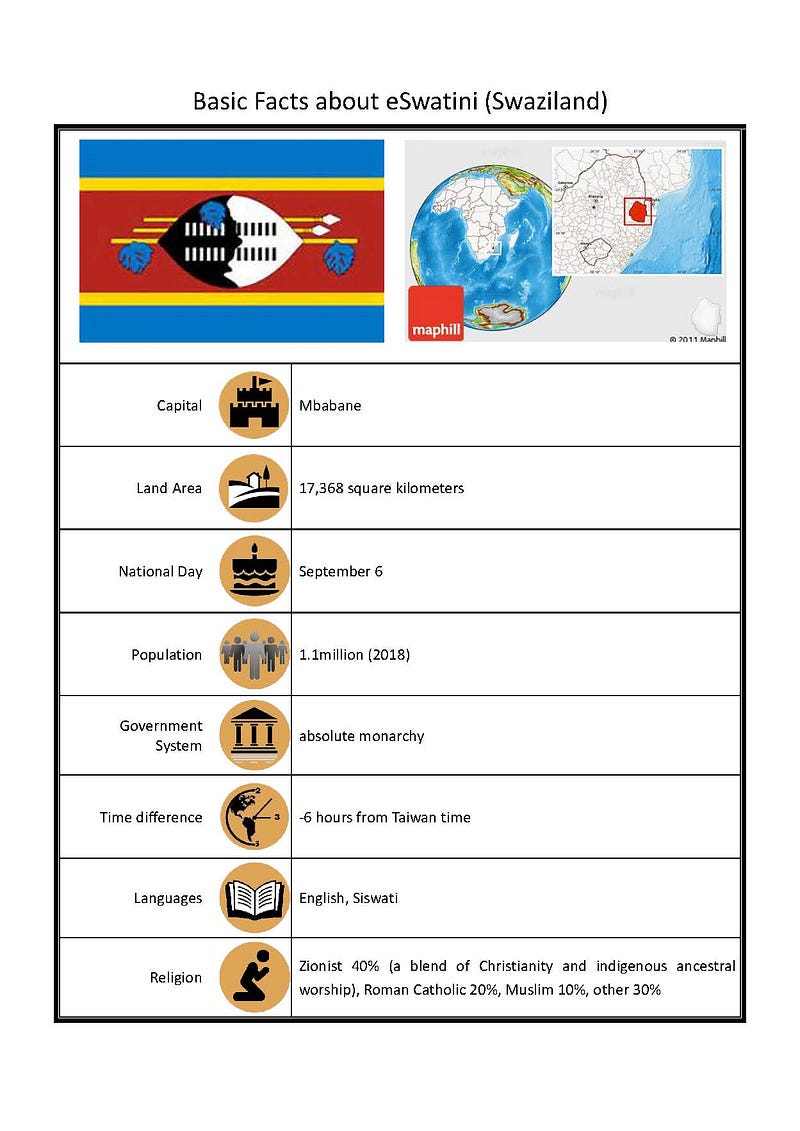

With roughly about 1.4 million people, Eswatini (formerly Swaziland) is nearly 70 times lesser in size than South Africa. However, comparison of countries by size may sometimes be misleading. For instance, even though Eswatini is about 24 times bigger in size than Singapore (a South East Asian country), Singapore’s economy (in GDP terms) is by far larger than Eswatini’s (about 74 times). This is even as both countries don’t have key export commodities such as oil.

Comparing both countries’ startup ecosystems further leaves less than desired. The most recent Startup Genome’s 2019 Global Startup Ecosystem Report rates Singapore as the #14 global startup ecosystem in the world and identifies Local Connectedness as one of its strongest traits. Apart from ranking 4th in the world, highlights from the report include that Singapore’s startup ecosystem has an estimated value of $25 billion, far exceeding the global average of $5 billion. The ecosystem ranks #5 on the Global Startup Ecosystem’s Fintech sub-sector. Early-stage funding per startup in Singapore is $202,000. Output Growth Index of startups in Singapore is 8 out of 10, indicating meaningful growth in total startup creation, calculated in an annualized growth rate.

Part of the reasons why Singapore’s startup ecosystem has succeeded is because the Singaporean government supports young startups with its Startup Tax Exemption Scheme. The scheme exempts 75% of a company’s first $73,000 in income. Additionally, Singapore raised tax deductions for IP registration fees from 100% to 200% and qualifying expenses incurred on Research &Development from 150% to 250% in 2018. Thus, Singapore startups are able to put off paying taxes until they are larger and more established.

Below we examine why the startup ecosystem in Eswatini is yet to come of age.

Poor Ease of Doing Business

The latest World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business report ranks Eswatini as number 117 out of 190 countries in terms of ease of doing business .

Founders desiring to register a business as a Private Limited Liability Company in the country must pass through each of the following procedures: Preregistration (for example, name verification or reservation, notarization); Registration in the economy’s largest business city; Postregistration (for example, social security registration, company seal); Obtaining approval from spouse to start a business or to leave the home to register the company; Obtaining any gender specific document for company registration and operation or national identification card.

Each of these procedures starts on a separate day (2 procedures cannot start on the same day). Approximately, it takes about 12 days to obtain a trading license in Eswatini. However, a company might need more than one trading license if it does more than one activity. Each activity has a different license fee. For instance, if the company produces and sells its goods to the public.

No Noticeable Legislation Incentivising Startups

Eswatini has no legislated law granting incentives to its startup ecosystem or newly formed businesses. Although companies may be issued with a Development Approval Order (of up to a 10-year period) enabling them to pay only 10% as corporate tax instead of the standard flat rate of 27.5% applicable to all corporate entities, only Eswatini’s Minister of Finance is authorised by law to exercise such powers. The grant of a development approval order is also only applicable to approved new investment, business or development enterprises in manufacturing, mining, international services and tourism and which will not unfairly compete with existing Swazi companies. Swaziland and foreign investors are eligible to apply for this incentive but the application must be made by a company incorporated in Swaziland.

By concentrating the incentive only in the manufacturing, mining, international services and tourism sectors, and by placing the stringent requirement of Ministerial approval, the scheme may have deprived startups still struggling with raising initial starting capital from the opportunity of being granted such order.

Again, Eswatini’s National Policy on the Development of SMEs defines small enterprises as having assets of E50,000 to E2m (US$6500- 260,000), 4 -10 employees, and sales of up to E3 million (US$395,000). Medium enterprises have assets valued at E2–5m (US$260,000–650,000), up to 50 employees, and sales of up to E8 million (US$1,040,000). (E = symbol of Swaziland’s currency Lilangeni (SZL).

The purpose of this classification is not to provide support in terms of seed capital but to give exaggerated focus on the startup ecosystem — more or less pretending that a lot is being done for startups.

At policy level, the SME Unit in Eswatini’s Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Trade is responsible for researching and proposing changes to existing policy or developing new policy related to SMEs in such areas as finance and training.

Eswatini’s Small Enterprise Development Company (SEDCO) also provides business development services such as training on business management and registration of start-up ventures. SEDCO operates nine small industry estates and rents workshops to small business owners.

The SME Development Unit / Domestic Investment Department in Swaziland’s Investment Promotion Authority also provides extensive support to SMEs as well as operating a linkages programme to help establish business relationship between SMEs and larger enterprises.

However, no matter the extent of such policies, nothing could be more powerful as spread tax incentives, which small businesses or startups can access no matter how remotely located they are, as is the case with Singapore’s Startup Tax Exemption Scheme or South Africa’s Section 12J. Most of the times, only a handful of businesses may be selected for such trainings or linkages programmes.

The direct implication of the absence of these incentives is lack of appetite for equity investments by venture capital or private equity firms in Eswatini ’s startup ecosystem.

Read also: Why California’s New Employment Law Could Return All Logistics, Transport And Similar Startups In Africa To Square One

Low Rate Of Technology Adoption

One of the enablers of economic growth in modern times is the degree of adoption of technological innovations by locals of a geographical territory. For instance today, the eight most valuable companies in the world are all tech companies. As at 2007, only one tech business, Microsoft, was among the 10 biggest companies in the world. Increasingly, globalisation has meant that many of these brands have significantly captured larger chunk of the global economy.

A 2014 statistic indicated that South Africa’s ICT fuelled by technological revolution contributed 2.7% to South Africa’s overall GDP, a statistic which is larger than agriculture, but slightly shy of tourism’s contribution of 3.1%. In other words, for every R100 that the South African economy produced in 2014, R2.70 was due to activities related to ICT. In Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, the Information and Communications Technology’s (ICT) contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) stands at 13.8% as at September, 2019, a figure which may more than double Nigeria’s Oil and Gas contribution of 8.8% in two years.

Having noted the significance of technology in the growth of a country’s economy and by extension its startup ecosystem, the rate of internet penetration in Swaziland is still very low. As at 2018, only about 446,051 people in the country, representing a meagre 27.8 % of the entire Swaziland’s population have access to the internet. Compared to the East African country of Mauritius, these statistics are abysmally poor. Even though Eswatini is about 9 times larger than Mauritius in size (and even has more people than Mauritius), there are about 803,896 internet users as at Dec/2018 in Mauritius, representing about 63.2% of the Mauritian population. Unarguably, this is why the Mauritian ICT industry made a GDP contribution of 5.6% in 2017 for Mauritius. The implication of this is that so many activities are going on in the sector, and invariably the Mauritian startup ecosystem.

A major factor that explains this low rate of technology adoption in Mauritius is the poverty gap in the country. The socially and economically marginalised — particularly those at the intersections of class, gender, race or ethnicity — are unable to harness the Internet to enhance their social and economic well-being. Although the internet sector in Swaziland has since been open to competition with four licensed Internet Service Providers (ISPs), prices have however remained high and market penetration relatively low. Much of this is attributable to the country’s landlocked nature. As a result of this, the country depends on neighbouring countries for international fibre bandwidth. This meant that access pricing was high for many years, though prices have fallen more recently in line with greater bandwidth availability resulting from several new submarine fibre optic cable systems that have reached the region in recent years. Invariably, the startup ecosystem in Eswatini is also affected by lack of abundance of this.

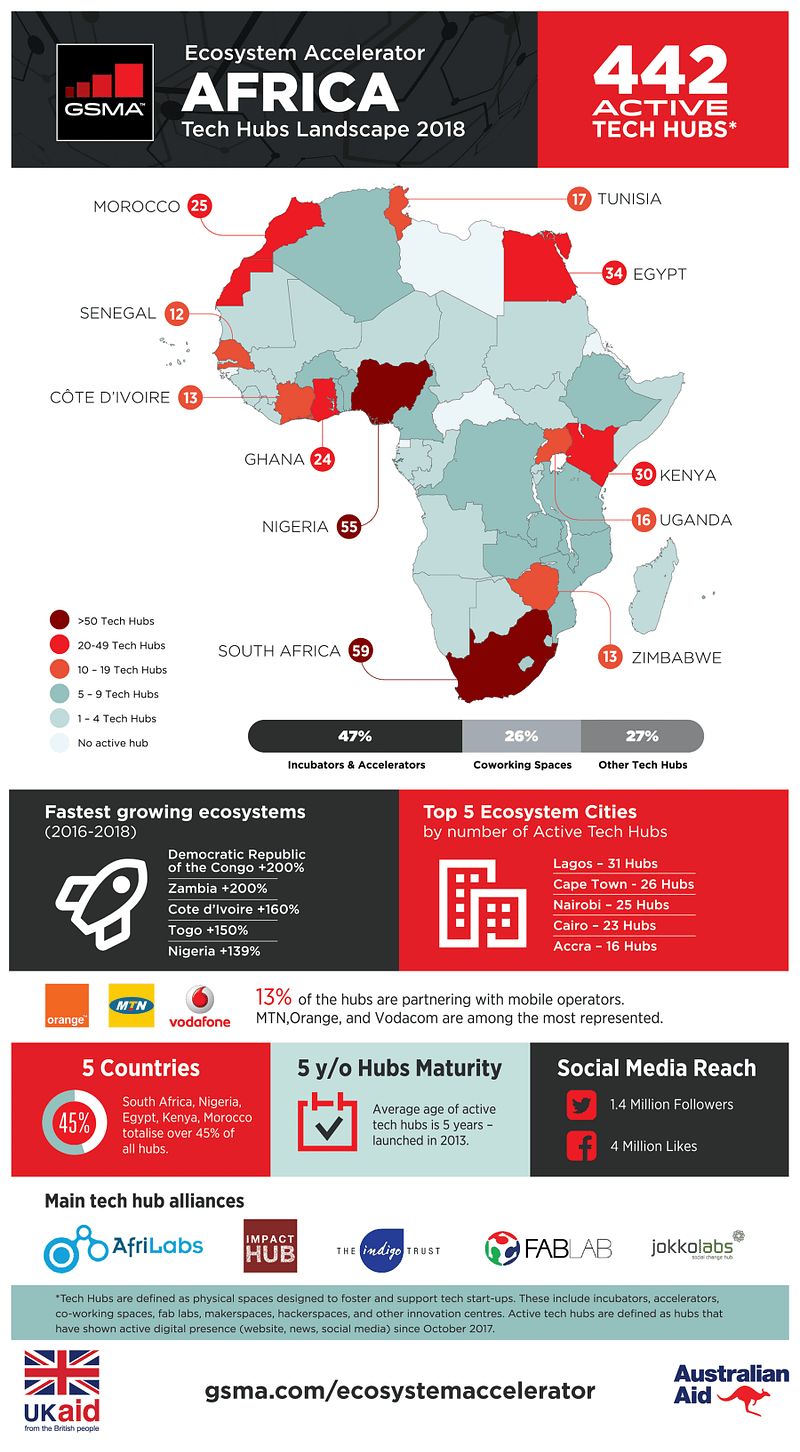

Low Number of Tech Hubs And Incubators

Unlike other African countries with appreciably large presence of tech hubs, incubators and accelerators, Eswatini boasts only of a few.

In Southern Africa, for instance, where Eswatini is regionally located, Zimbabwe and Zambia recorded remarkable growth respectively doubling and tripling their number of active tech hubs in eighteen months in 2018 (13 vs 6 in Zimbabwe; 6 vs 2 in Zambia). However, there is only about one hub in Swaziland, out of over 420 hubs present in Africa. The Mbabane Hub is made up of young people in their own right, working together to promote technological innovations around the Mbabane city region— the capital and largest city in Eswatini.

Although the Swaziland government has, in 2012, initiated the Royal Science and Technology Park (RSTP), a parastatal under the Swaziland Investment Promotion Authority (SIPA), very much still remains to be done. The Biotechnology Park which falls under The Royal Science and Technology Park (RSTP) is situated at Nokwane and is a “one stop facility” that creates an enabling environment to investors wishing to settle within the Royal Science and Technology Park. RSTP hopes to foster the conception of inventions and facilitate their patenting and to help knit various elements of the Research & Development (R&D) cluster together. By 2022, RSTP hopes to have trained Swazis with new, innovative skills, providing them with the environment to experiment on new technologies. RSTP also hopes to inculcate a culture of entrepreneurship among Swazi graduates and to facilitate specially promoted research in response to national priorities and develop strategies for the development of human resources in Swaziland.

The importance of tech hubs, incubators or accelerators in the development of Eswatini ‘s startup ecosystem, for instance, can never be over-emphasized. Tech hubs can create an environment specifically targeted at helping young technology companies thrive by encouraging experimentation, not demonizing failure, and helping firms network with other like-minded individuals and enterprises. They can also make it easier for firms to meet investors in order to get their project funded.

Bottom Line

Eswatini still has a long way to go in terms of its startup ecosystem growth. However, it has a bright future on the flip-side. The country has a median age of 20.5 years, although with a life expectancy of just 31.88 years, the lowest documented life expectancy in the world and less than half the world average (largely because of large prevalence of several health issues, including HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis). With increasing accessibility to the country’s economy by foreign investors, most of whom are from South Africa, there may still be some hope on the horizon.