When Venture Capital firm Vestox New Ventures participated in Swvl ’s last Series B-2 $42 million funding, little did it know that it was becoming part of a never-before-seen future in the African transport ecosystem. If Egypt’s Swvl continues in the manner with which it has been known in recent times, it would most probably be the only African startup in the transport sector to reach a unicorn status in the next 7 years or more. At the last count, Swvl, the Egyptian ride-sharing startup, is now over $160 million in value, beating any known Africa-owned transport or logistics startup both in funding and rate of expansion. First in Egypt, then quickly in Kenya and Uganda, before shooting off to Pakistan, with hopes of sealing off 2020 with major expansion to the Philiphines, Bangladesh, Indonesia or Nigeria, Swvl is finally home to roost. In the highly fragmented and chaotic African transport sector, if Swvl gets it right, it would care less about fintechs or other short-term money-spinning initiatives.

‘‘We believe the overall target of $1 billion in Gross Merchandise Value by 2023 is achievable,’’ notes Vestox, in a recently published financial report. ‘‘Egypt alone could become worth at least $500 million and, if successful in Lahore, Karachi, Nairobi, Lagos and Johannesburg, this upside obviously multiplies,” the report further reads.

The report is further optimistic given that overall total addressable market in emerging markets’s transport sector is estimated to be at some $150 billion, with Swvl’s cohorts and bus lines in Cairo reaching a 60%+utilization rate, Swvl is headed for a clear path to gross margins which is close to 30% over time, higher than taxi-hailing at roughly 20%. This would likely warrant higher multiples for this type of business, says the report.

It is however not rocket science that the startup has come this far. Swvl’s success rate could be attributed to the following factors:

A Compelling Product That Adjusts To The Cultural Behaviour Of A City

‘‘Better than a public bus

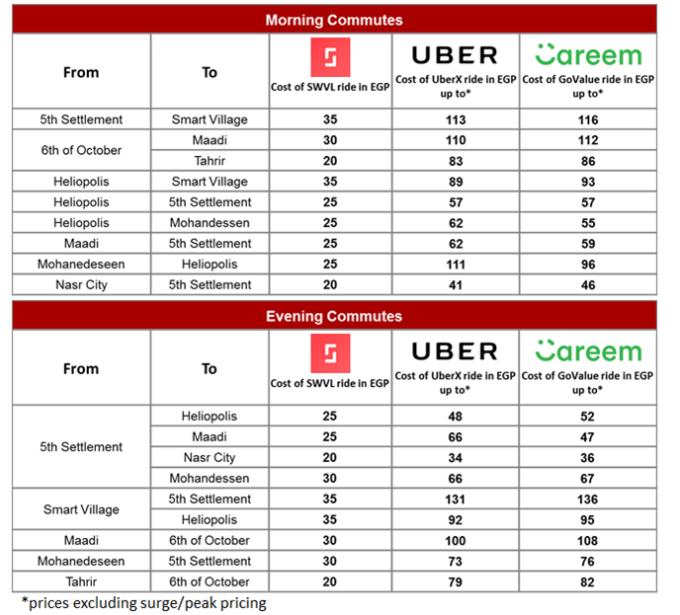

✅ Cheaper than an Uber

✅ WiFi equipped

✅ Comes on time, every time.

We’re all part of the traffic problem. Become part of the solution. Use Swvl,’’ Swvl notes on its official Facebook page.

This is what Mostapha Kandil and his team got right. A former employee of the over $2 billion valued Careem, now acquired by Uber in a $3.1bn deal, Mostapha Kandil notes that around the world, public transportation is a loss-making machine. If you can take this load off the government and privatise it in a way that is super cheap and create job opportunities, you are revitalising a sector, he said. To address this, Swvl looked at the following metrics:

- Cairo, where Swvl would launch its pilot project, is Africa’s most populous metropolitan city, boasting a population of over 20 million people, with every highway, road, and alleyway clogged with cars and motorbikes spewing fumes into the air.

- There are many options for navigating the city of 23 million people considered the most populated. With a whopping 4 million daily riders on its three lines, the Cairo Metro is half the size of the Washington D.C. Metro and carries four times as many passengers per half-mile of track. The public bus system is similarly outmatched. Among the world’s major cities, Cairo has one of the lowest numbers of buses per million residents .

- The most used, and most important, part of Cairo’s transit system is the microbuses, a network of semiformal private vans that are ubiquitous on the streets of Cairo (and most African cities). While dirty, cheap and with lines all over the city, microbuses are known for driving at dangerous speeds, packing in as many passengers as they can, and ignoring traffic laws.

- With Egypt already one of Uber’s fastest growing markets in the world at the time of Swvl’s launch, with more than 40,000 Egyptian drivers working on the platform every month, and new drivers joining up at the rate of 2,000 a week, there was no gain fighting Uber already with the monumental capital base.

- Swvl was therefore launched as a product that would find a niche, almost avoiding Uber’s model which most times is expensive and does not often bring the 27. 8% of Egypt’s population that were living below poverty line into its net. The Swvl product would however still retain the city’s culture of minibuses but in a disruptive way. This strategy hoped to reduce the number of cars on Egypt’s congested highways because the cleaner the mode of transport, the more attractive it would be for upper class users.

- Swvl then works by connecting commuters with private buses, allowing them to reserve seats on these buses and pay the fare through the company’s mobile app. The buses available on Swvl operate on fixed routes (or lines).

- So when Mostapha Kandil and his team pulled the trigger, a different product was launched, way out of Uber or Careem’s way, and way into the culture of the city.

In A Crowded Ecosystem, Startups Need Enough Funding To Stick Out

Mostapha Kandil didn’t just quit Careem to be a watcher. Not doing feasibility studies of the market he was about to enter would most probably mean harm and dead on arrival for Swvl. At the time Softbank made an investment in Uber in 2017, Uber was already overshooting a valuation of about $48 billion. Careem, the Uber of the Arab world had already concluded its US$350 million Series D round, based on a $1 billion valuation for the company. Indeed, to illustrate the extent of Careem’s influence, Swvl’s first round of funding saw Careem investing $500,000 for a minority stake in the company, although Careem’s investment could best be described as a parting gift to Kandil who was previously an employee in Careem.

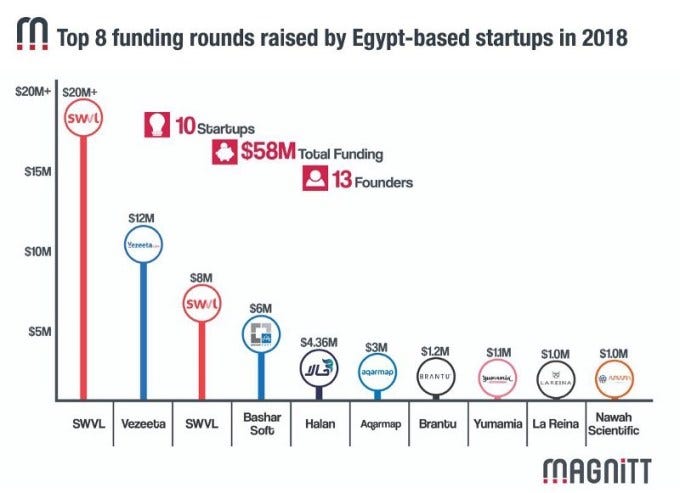

To further show that Swvl’s team was mindful of power of funding in confronting industry giants in the likes of Uber and Careem, of the total amount of about $686.4 million raised by African tech startups in 2018, Egypt got a share of $68 million. Out of Egypt’s share, SWVL got about $38 million backed by some of top regional VCs including BECO Capital, Raed Ventures, Oman Technology Fund, and global names like Endeavor Catalyst, making the startup the most-funded Egyptian startup.

Kandil said the company is seeking to raise more than $100 million in a financing round in the first half of next year, and is targeting a $1 billion valuation in the next five years.

This long-term focus on sustained funding ensured that when Uber and Careem entered the Egyptian public bus service as Swvl, Swvl had already captured a significant market share and had enough capital. Swvl’s application has been downloaded for well over 360,000 times on Google play store and Apple iStore. The platform completes 100,000 rides monthly.

“This year (2019), we have entered about seven new cities and next year we are targeting another 10 to 20 new big cities,” Kandil said. “We aim to reach one million trips a day in Egypt over the next five year.”

Although with Uber’s acquisition of Careem, Swvl may be headed for a more stiff fight for a market share in Egypt, the startup’s expansionist agenda has kept it far away from attrition.

‘Obviously, I am very happy about the fact that my team and I have reached this far in such a small amount of time,’’ Kandil said. ‘‘When we first came into this space, everyone thought we are crazy. They thought we are taking on Careem & Uber and we wouldn’t be able to survive. No investor was willing to take us seriously. This investment…proves that we can actually make it.’’

Swvl’s Team Executes Well And At High Speed

Mostapha Kandil built a strong team in Swvl. When Careem made its first investment in the startup in 2017, it noted that the team run, learn and develop at a very high pace and high agility. This is perhaps what has kept Swvl ahead of other startups started in the same year. In early 2019, Swvl announced plans to pour over $14 million in Kenya. The company partnered with BRCK for free wifi in its buses in the East-African country. In June 2019, the company raised US$42 million for its expansion in Africa. In July 2019, it expanded its operations to Pakistan, starting with Lahore. In September, it expanded its operations to Karachi, and Islamabad. The company has also announced that it has plans to invest $25 million in Pakistan.

‘‘Previously at Rocket and Careem, Mostafa Kandil has built a team that executes well and at high speed,’’ says Vestox stated in its published financial report on why it was part of Swvl’s Series B-2 $42 million round. ‘‘In fact, we believe that Mostafa may be the first Arab (and indeed African ) tech entrepreneur that builds a global product.’’

One of Kandil’s strategies is never to over-engineer everything. Just get it done, he said. You’ll figure it out on the way. Kandil said he learns more by learning faster. If you do 9 experiments a week and your competitor does 10 experiments, then your competition ends up learning 52 times more over a year, he said.

There Is Something About Swvl’s Partnerships

What makes Swvl different from its competitors is because of its series of partnership deals. The startup recently signed an agreement with Ford motor company, to deploy more cars on the road. The agreement will combine the brilliance of the Ford Motor Transit, world’s best-selling van brand, with an app-based mass transit system that enables commuters in Egypt’s major cities to enjoy an affordable, convenient, safe and reliable alternative to existing transportation services. Ford Transit, which the startup intends to use is already the third best selling van of all times. SWVL is already in possession of about 100 Ford Transits. Hazem Taher, SWVL’s Head Marketing Manager, said the vans were ready to go and they’re excited to push them on SWVL’s routes.

This agreement not only gives SWVL an advantage within the Egyptian private transport market, it also, by some distance, allows it to broaden its reach in the MENA (the Middle East and North Africa) market.

‘‘I think we are in uncharted territory when it comes to expansion, when it comes to growth for an Egyptian startup,’’ Kandil said. ‘‘We feel that this is our responsibility, and we are committed to bringing what we have done in Egypt, scaling it even further and bringing it to the rest of the emerging markets.’’

Charles Rapulu Udoh

Charles Rapulu Udoh is a Lagos-based Lawyer with special focus on Business Law, Intellectual Property Rights, Entertainment and Technology Law. He is also an award-winning writer. Working for notable organizations so far has exposed him to some of industry best practices in business, finance strategies, law, dispute resolution, and data analytics both in Nigeria and across the world