While funding accruing to the African startup ecosystem from venture capital firms is increasing year-on-year, the number of startups involved in the funding are relatively small compared to available data about the number of startups in Africa. In 2019, for example, while a platform like VC4A listed a total of 13,500 startups in Africa, only about 427 startups raised over $2 billion in funding. This means that if you are a startup in Africa, you are only about 3% more likely to raise funds from venture capital firms. Again, this possibility increasingly varies depending on which African country your startup has its headquarters or is operating in. According to a recent report, between 2014 to 2019, venture capital investors preferred to invest more in startups in Southern Africa (mostly South Africa, etc.), with the region getting about 25% of all VC deals; followed by East Africa — Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda , etc. — (23%); and West Africa (21%) — Nigeria, Ghana,etc. While other African countries shared the remaining 31%, Egypt, and other North African countries are also proving to be good destinations for startups in terms of funding.

Why then are many startups still left out in the whole funding bubble? An attempt will be made to provide answers to this.

Poor Understanding of How Venture Capital Funding Works

This is a foundational challenge that confronts most startup founders across Africa. There is an overwhelming disconnect among many founders about what venture capital, and not investors generally speaking, really means. The ability to know the difference between venture capital and angel investors, bank loans, funds from family and friends, or grants is what makes the whole difference between founders who have raised funds for their startups through VCs and those who have not.

Prior knowledge of venture capital, even before setting up a startup company, is very vital for startups desiring to raise funds from VC investors in the future. At the earliest stage, such knowledge would not only assist them in choosing their business ideas, but would also help them in properly structuring their business entities so as to suit the structures usually prefered by VC investors.

Fundamentally speaking, unlike banks that give you only loan and expect interest payment and repayment of the capital sum after a period of time without desiring a stake in your company through the loans, a traditional venture capital company usually takes up ownership stake (shares) in your company, while providing you with the desired capital to run your business, in anticipation of future returns on its investments (usually, also, at an agreed percentage). Venture capital is also different from grants because grants are free money to businesses while venture capital is not.

Knowing these differences will therefore assist startups in choosing what type of business idea to pursue (since VCs are mostly interested in high-growth startups with long-term growth potential); and what structure of business to adopt (since VCs are also interested in taking up shares in the business, or even sitting on its board).

Thus with this explanation, it may be more difficult for a small business which was not structured as a company and which sells fabrics on a small scale to secure venture capital than for another business structured as a company, and which runs a piggery, and has a plan of leveraging technology to expand its market, or which, even though does not leverage technology, has such potential as to so quickly grow and expand across locations and to different markets.

“VC is relevant for high-growth companies. Taking money from VCs and then not growing very fast is the source of many headaches and grey hairs,” says Jean-Claude Homawoo, co-founder and chief product officer at Lori Systems, one of Africa’s bigger fundraising success stories.

“When you take on that money, that money needs returns, and it is a big responsibility. You have to scale the company,” Etop Ikpe, CEO of Nigerian company Cars45, another startup that has successfully raised funds, adds.

The Products/Services And Their Sectors Matter

This is another fundamental problem hindering many startups in Africa from accessing funds from VCs. Indeed, VCs are also business people who, like startups, are out to make money. There may be VCs whose guiding investment values support promotion of social or environmental projects or causes, but a majority of VCs get their funds from other investors, such as pension funds and high net-worth individuals, and therefore, are expected to be accountable and make profit on their investments.

Indeed, acquainting oneself with knowledge of which sectors have attracted VC funding most in Africa in the past should form one of the earliest guiding principles in choosing which startup idea to pursue, although market size, market fit and strikingly innovative solutions (check out South Africa’s SweepSouth, for instance) and overwhelming passion from founders have always dragged investors’ interests into new areas.

Again, since startups are themselves largely untested territories (considering that a majority of them have not existed for an appreciable length of time nor have they been affected by policy changes or market trends), investors tend to stick more to sectors that have proven to return most highly on their investments.

“It is really pattern recognition; they see the kind of deals that have happened in the past and they try to mimic that,” says Homawoo. “They (investors) look for the same makeup over and over again. So for founders that don’t look like those that have raised in the past there is a hurdle. That’s something that we have to break.’’

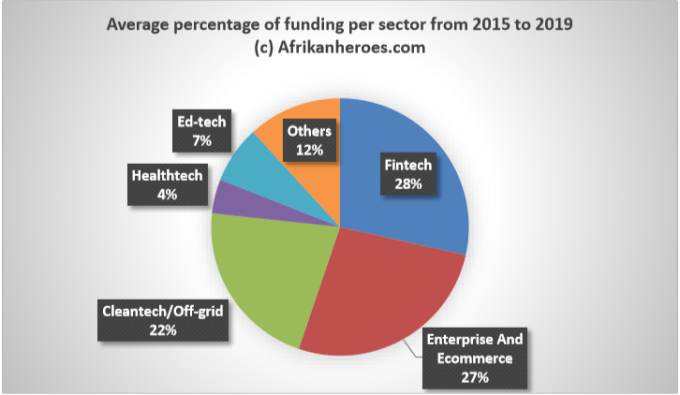

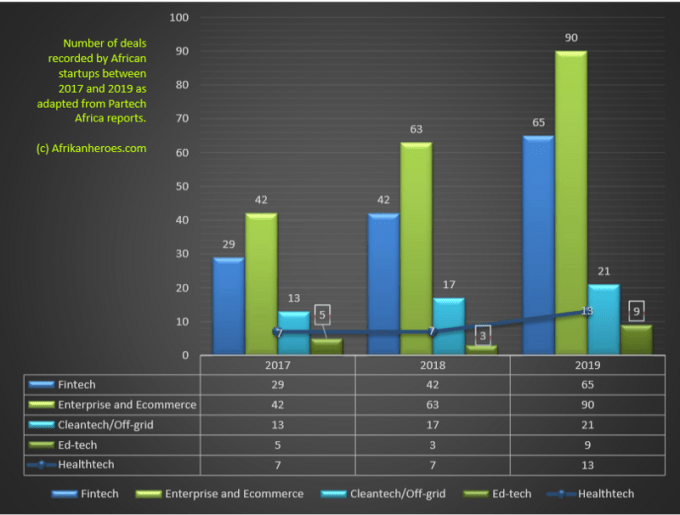

As an instance, until now, much of the investment on the African startup space has gone more to other sectors than healthcare. In 2019 alone, out of a total of 250 deals amounting to a record-breaking $2.02 billion reported by data firm Partech, financial technology companies (fintechs), at 41%, received the lion’s share of the whole investment sum. The set of data below further paints this picture better. From the data, healthcare startups in Africa have managed to secure only about 4% of the total funding raised by African startups in the past four years, compared to the increasing interests shown by investors in other sectors, such as fin-tech (which, at 28% has netted the highest percentage of funding coming to African startups) or enterprise and eCommerce( 27% of the total funding accruing to African startups).

Also worrisome is the fact that investors, until the descent of the coronavirus, had not shown much interests in the African healthcare startup ecosystem compared to others . This perhaps explains the fact that in the past three years (2017–2019), healthcare startups in Africa only closed 27 deals (a majority of them being follow-on or new rounds of investments, as against investment in entirely new healthcare ventures). 27 deals is so meager compared to what fin-tech or enterprise and eCommerce (at 136 and 195 deals respectively) got within the same period.

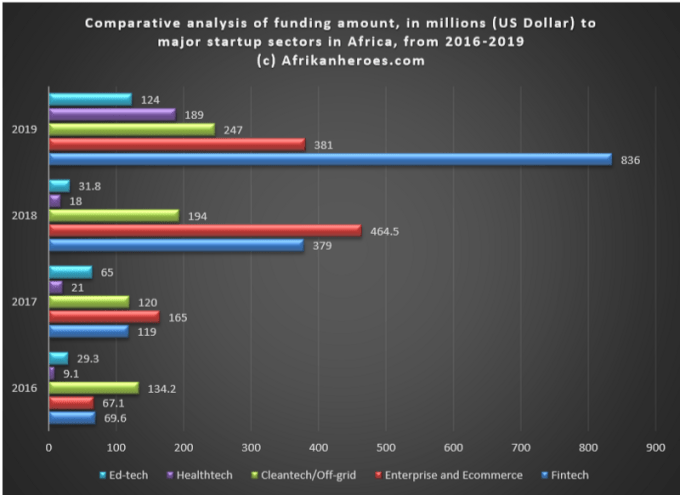

The worst fact about investment in the African healthcare startup space is however yet to come: out of a jaw-breaking $4.1 billion received by African startups in total in four years (2016–2019), healthcare startups only boast of a meagre $237.1 million.

This is far behind what sectors such as fintech or enterprise and ecommerce ( at $1.4bn and $1.07bn respectively) secured during the said period. (For fuller version of all the sectors and how VCs have invested in them click here.)

Therefore, it is recommended that African startup founders, desirous of securing funds from venture capital firms, first study the investment patterns, over the years, of Africa-focused VCs in order to get an insights into how their startups may be affected.

Team Is Everything

Startup founders should not underestimate investors’ bias about who the team members are. In most instances, the choice by VCs, of which team to work with has always, from practical experience and from facts, been influenced by such things as age, gender, race, class, educational background, previous experience founding a startup, nationality or even social networks.

However, while we may not change our individual identities to attract investors, it pays to be strategic. For instance, even though a startup’s founding team may entirely be constituted by persons who are newbies to the startup environment or who have not had any previous experience founding successful startup companies, it pays to have a strong team of advisors/board members, or persons of influence projected prominently behind the team. Investors are more tended to finance who they can trust; who has strong credibility and integrity and who knows their mettle about the sectors they are playing in. The more dense the team, in terms of character, value or influence, the chances of the startups securing funding any time soon. Below is a table of some African startup founders and their pedigree.

| S/N | Name of Founder | Company | Age Bracket | Extra Information |

| 1 | Tunde Kehinde | Jumia | 20-30 | B.B.A (Howard) MBA (Harvard); One year experience before co-founding Jumia. |

| 2 | Iyinoluwa Aboyeji | Andela | 20-30 | B.A., Legal Studies (Waterloo); Two years experience before co-founding Andela. |

| 3. | Xavier Helgesen | Zola Electric | 30-40 | MBA Oxford; Previous CEO and 8 years previous experience. |

| 4 | Fara Ashiru Jituboh | Okra | 20-30 | B.A (North Carolina); Previous 9 years IT experience. |

| 5 | Yinka Adewale | Kudi | 30-40 | B.SC (Ife, Nigeria); 4 years previous IT experience. |

| 6 | Obi Ozor | Kobo360 | 30-40 | B.A (Pennyslavia); 6 years previous experience, including at Uber and J.P Morgan. |

| 7 | Franklin Peter | Bitfxt | 20-30 | B.Sc (Nsukka, Nigera); at least one year previous experience. |

| 8 | Elia Timotheo | East Africa Fruits | 30-40 | B.A (Mzumbe, Tanzania); 8 years previous working experience. |

| 9 | Aretha Gonyora | Payitup | 30-40 | B.A (Zimbabwe); 3 years previous experience. |

| 10 | Aisha Pandour | SweepSouth | 40-50 | P.HD (Cape Town, South Africa); 8 years previous experience. |

| 11 | Adegoke Olubusi | Helium Health | 20-35 | B.Sc. (Maryland, USA); 3 years previous experience, including at eBay, Paypal, Goldman Sachs) |

| 12 | Adetayo Bamiduro | Max.ng | 30-40 | MBA (MIT, USA); Over 10 years previous experience. |

| 13 | Gregory Rockson | mPharma | 30-40 | B.A (Westminster, UK); Over 10 years previous experience, including WEF Global Shaper. |

| 14 | Trevor Gosling | Lulalend | 35-45 | B.A (Pretoria, South Africa); 10 years previous experience, including at Goldman Sachs, Rand Merchant bank. |

| 15 | Rapa Ricky Thomson | Safeboda | 30-50 | No education history; Natural entrepreneur with previous experience in transport. |

| 16 | Onyeka Akuma | Farmcrowdy | 30-40 | B.Sc (Sikkim Manipal, India); Over ten years previous experience. |

| 17 | Ahmed Wadi | MoneyFellows | 40-50 | B.Sc (Stuttgart); 5 years previous experience, including at National Bank of Kuwait. |

| 18 | Abraham Cambridge | Sun Exchange | 40-50 | B.Sc (Sussex); Over 10 years previous experience. |

| 19 | Deji Oduntan | Gokada | 30-40 | MBA (Cornell, USA); Over six years previous experience, including at GTB Bank, Jumia. |

| 20 | Karl Westvig | Retail Capital | 50-60 | B.Sc (Cape Town, South Africa); Over 20 years experience. |

| 21 | Femi Adeyemo | Arnergy | 40-50 | M.Sc (Stockholm, Sweden); Over 10 years experience in the IT space, including at Huawei. |

| 22 | Meshack Alloys | Sendy | 30-40 | M.Sc (Nairobi, Kenya); Over 7 years experience in the IT sector. |

| 23 | Tosin Eniolorunda | TeamApt | 30-40 | B.Sc (Ife, Nigeria); Over 8 years previous experience, including at Interswitch, |

| 24 | Gilbert Blankson-Afful | Sumundi | 30-40 | B.Sc (Ghana); Founded Sumundi immediately after education. |

| 25 | Adan Mohammed | Ecodudu | 30-40 | B.Sc (Kenyatta, Kenya); Founded Ecodudu immediately after education. |

| 26 | Prince Kwame Agabata | Coliba | 30-40 | B.Tech (Ghana); Founded Ecodudu immediately after education. |

| 27 | Belal El Borno | Yumamia | 35-45 | B.Sc (AASTMT, Egypt); Over 10 years previous experience, including at Kuwait Food Company. |

| 28 | Mohammed Youssef ElBaz | Zedny | 50-Above | MBA (Arizona, USA); Over 10 years of previous experience. |

| 29 | Neto Ikpeme | WellaHealth | 35-45 | MBBS (Dublin, Ireland); Over 5 years previous experience. |

| 30 | Benji Meltzer | Aerobotics | 30-40 | B.Sc (Cape Town, South Africa); At least 5 years previous experience, including at Uber. |

| 31 | Timothy Mwangi | Amitruck | 35-45 | B.Sc (MIT, USA); Over 9 years previous experience, including at Oracle, USA. |

| 32 | Mostafa Kandil | Swvl | 30-40 | B.Sc (Cairo, Egypt); At least 2 years previous experience, including at Careem. |

| 33 | Temidayo Isaiah Oniosun | Space In Africa | 20-30 | B.Tech (Akure, Nigeria); At least 3 years previous experience. |

| 34 | Waleed Abdl El Rahman | Mumm | 35-45 | B.A (Cairo, Egypt); Over 10 years previous experience, including at Procter & Gamble, Lebanon. |

| 35 | Geoffrey Mulei | Tanda | 20-30 | B.A (Malaysia); 2 years previous experience at former startup. |

| 36 | Stone Atwine | Eversend | 40-50 | B.Sc (Mbarara, Uganda); Over 10 years previous experience, including at Alliance Francaise. |

| 37 | Fatoumata BA | Janngo | 30-40 | M.A (Toulouse, France); Over 8 years previous experience, including at Jumia. |

It should be noted, however, that a majority of the founders listed above, whose startups have secured VC funding, represent a tiny portion of the entire ecosystem of startup founders in Africa. It should also be noted that all extra information as provided, even though may be of some considerable importance to some VCs, may not be to others.

True entrepreneurship is not bestowed solely on the basis of educational qualifications or age, as can be found above. Of course, there are thousands of entrepreneurs and startup founders scattered across Africa (most of whom are running successful businesses) who may not fit into the qualifications above. What is only stated here is that, given that there are not many VC firms operating on the continent, like it is obtainable elsewhere in the world, it only pays to be strategic enough, through a strong team, to be able to access the limited ones available.

Bad Pitch Processes

Any startup desirous of raising funds anytime soon must bear in mind that investors receive humongous amount of pitches from startups around the world on a regular basis and that it pays to stand out. As a matter of fact, a recent report by DocSend found that investors spend a little over 3 minutes, on average, reviewing pitch decks that were sent to them by founders.

From experience, most startup founders, in a bid to protect their intellectual property, often hide relevant information from investors. In as much as it pays to protect one’s intellectual property, it also pays to determine what information is material enough to be excluded from investor’s early scrutiny. “You can’t keep trade secrets from your investors,’’ says Barry Schuler, managing director at DFJ Growth, one of the first venture firms to focus on growth as a specific practice and an investor in Twitter and Tesla. “The number-one sign of complete transparency is an entrepreneur who says, “I don’t know the answer to that question, but I will get it to you.”Barry adds.

Generally, at a glance, a good startup pitch deck should, among other things, have a strong value proposition, and must give a sufficient clue about how the startup intends to utilise the proceeds of the investment it seeks to secure from the investor.

“People come to me and say they are playing in whatever market,”says Andrea Böhmert, co-managing partner of South African VC firm Knife Capital, “but when we really drill down, their value proposition puts them in a different market. You need to be able to define your value proposition. And then based on that your market. And then understand your numbers and how big that market is.”

Apart from constructing a precise value proposition, a pitch deck must also provide an in-depth guide on how the startup can make returns on the investor’s funds. No investor would be willing to commit hard-earned currencies into a project that has no clear plan on how to spend the money.

“Sweat the financial details,” says Victoria Fram co-founder and managing director of VilCap Investments. “ You need to show an awareness that one of your jobs is to not run out of cash. You need to speak intelligently on dilution and valuation. Say why you’re raising a given amount, what milestones that money will allow you to achieve, and what milestones come next.”

However it goes, always remember to keep your deck concise enough. Whether it is Venture Capitalists or Angel Investors that you are pitching to, keep your deck focused. As VC Iskender Dirik notes, “The attention span of a VC is even shorter than you might think. Be as striking, simple and short as possible.” (source). Similarly, Angel Investor Jordan Rothstein says that one of the key factors in creating a great pitch deck is keeping it “clear and concise” (source, Angel investor).

And finally be transparent with your disclosures when you have established a fair confidence in the investors. To learn how to bounce back from a failed pitch effort click here.

Pitching The Wrong Investors

Nothing could be so frustrating as pitching the wrong investor. Consider the waste of time and resources!

African startup founders usually make the mistake of assuming that most VCs are sector-agnostic. The fact is that while some VCs would prefer to invest in exceptionally ground-breaking solutions that are outside their sectors of focus, the opportunity to do so don’t always present themselves. It therefore behoves on startup founders to first research on active investors in their sectors of focus. This will assist them not only in reducing the time and resources spent scouting for investors, but will increase their chances of landing funding anytime soon.

“Lots of first time entrepreneurs don’t take the time to put together their thoughts,” says Ian Lessem, managing partner of South African investment and advisory firm HAVAÍC.

“If you want to attract VC funding from the US you must understand that companies involved are servicing much bigger businesses serving much bigger markets. If you have no plans to scale outside of South Africa, you would be naive to think a US VC would be interested.”

For African startups playing in the healthcare industry, this link will lead you to a list of active investors in that industry.

Gain Traction

In as much as a recent report says that nearly one third (32%) of the total number of early-stage investments reported in Africa between 2014 and 2019 were seed stage deals, these deals, however, accounted for only 5% of the total deal value, showing that while more investors were investing at the seed stage than at any other stages, they weren’t pouring in more in monetary sums into the startups compared to the amount invested at other stages.

One more way to stand out as an African startup is, therefore, to gain traction. The African market is often referred to as an emerging market because it has not entirely shed its traditional economic focus that relied more on agriculture and the export of raw materials. Hence, investors often regard such markets as highly risky, and therefore deplore greater caution in their investment strategies when investing in them.

“Traction: It’s what investors everywhere are looking for in order to determine whether to anoint your startup,’’ writes Mike Belsito in his book Startup Seed Funding for the Rest of Us: How to Raise $1 Million for Your Startup — Even Outside of Silicon Valley.“the next big thing” and inject the cold, hard cash needed to accelerate your business. If you can’t find traction, forget raising capital — your business will struggle just to stay alive. Find traction, and raising capital will never be an issue for you. It’s important, however, to understand what traction really is — and what it isn’t.”

This writer wishes you great success and luck in your fund-raising journey. The journey may be hard, but always remember that patience, almost always, pays; plus you are always one pitch away from getting a signed term sheet.

Charles Rapulu Udoh

Charles Rapulu Udoh is a Lagos-based lawyer who has advised startups across Africa on issues such as startup funding (Venture Capital, Debt financing, private equity, angel investing etc), taxation, strategies, etc. He also has special focus on the protection of business or brands’ intellectual property rights ( such as trademark, patent or design) across Africa and other foreign jurisdictions.

He is well versed on issues of ESG (sustainability), media and entertainment law, corporate finance and governance.

He is also an award-winning writer.